Written by James Muat-Dodd and Connor Wakefield

The current paradigm; guerrilla marketing and social media

In our modern time, music marketing is more

impactful than ever. The internet put the power of demographics, targeting and

distribution in the hands of any person willing to look for it. However, in

this new environment competition is more prolific than ever and this wide

accessibility has led to more necessity now than ever to think in new, creative

ways, in order to stand out.

One of the first things that comes to mind when online marketing is mentioned

is advertisement and while this is true to an extent, social media has created

cults which avidly share information and content with each other at no cost.

Social media also have within them, a form of advertising; dependant on a concept which has come into its own since the widespread use of the internet, ethnography. “Ethnography draws on a family of methods, involving direct and sustained contact with human agents”…”It results in richly written accounts that respect the irreducibility of human experience” (O’Reilly, 2009). Now traditionally ethnography has been very closely tied to qualitative research, as above states it requires “direct and sustained contact with human agents”. However, thanks to the internet age, the form that this sustained contact takes has begun to shift.

Companies like Facebook and YouTube have the power to monitor users and their usage history of their services and build a profile which logs what content users are looking at. While this method has proven reliable and is far from a secret (managing to become the basis of a targeted ad system Facebook runs internally and the basis of the recommended video system within YouTube) it’s not the golden ticket to internet fame. With further optimization we could potentially see mass ethnographic data able to be collected quickly on a large scale, but it still couldn’t guarantee a sale.

So the question remains, how can a person

grow a fanbase without online advertising? “How else can you connect with your

fans than through social media? In order to increase your bottom line, you must

focus on your fans. So stay in touch with them.” (Ramaut, 2014) this quote gets

to the heart of online advertising. Through social media, a distinct style and

regular posts, a person who’s no more than a personality can develop a

following, never mind a musician. This following can then be nurtured and grown

into a fanbase without any money being put into advertising.

This is largely due to the internet and social media bypassing the old

gatekeepers and distribution streams of the industry. As the internet has become

more popular it’s allowed artists to market and distribute their content to the

world in new ways. The most prevalent of which being streaming services such as

YouTube, Spotify, Apple Music and SoundCloud. However, a problem does occur

with these new distribution streams “as widely reported in the media, many

artists and record labels have criticized the small remunerations received from

these services”. (Kaitajärvi-Tiekso, 2016)

Modern distribution, monetary shortcomings and alternative success

Unfortunately these widely accessible distribution tools do come at a cost, they make significantly less money than physical releases on average, with a total of “336,842 total plays to earn $1,472” (Sanchez, 2019) on Spotify, one of the current largest players in the streaming industry. By contrast, a $5 album would only need to be purchased 295 times to make more than this amount.

So how can an independent artist make money? Well, currently a strong trend is live performance, however if you redefine what constitutes commercial success for a musician, we start to see alternative methods of income from musicians.

As mentioned previously, a personality with clear branding and regular content can develop a following in our modern age. What if we were to take this basic model of a content creator on a streaming site such as YouTube and brand them from the ground up?

Well, a few artists which fall into this description already exist, one of which has been creating music endlessly for years and the other which started recently.

Andrew Huang

Andrew Huang has been creating music related videos since at least 2011, at the time of writing he’s approaching two million subscribers. His content gently tiptoes a fine line between vlog and music production. Often travelling to specific places and showcasing peculiar gear and then resolving to making music relating to the video’s events.

This is a new kind of success not seen before in the music industry, a musician who makes significant money off products other than music and merchandise. Not only this but his explorative nature when it comes to audio production and relatively high profile status allows him access to free music gear, which for an independent artist is an extraordinary bonus.

Strictly speaking however, Andrew Huang doesn’t make most of his money from just his music.

A look at his Spotify artist page reveals less than 64,000, bringing him barely up to our “336,842 total plays to earn $1,472” (Sanchez, 2019) stat from earlier, that’s if each of these listeners listened to a song of his a little over 5 times a month on average.

The issue with the model Andrew Huang has presented is that he’s experimental in his music, often using wild, outlandish noises that have usually been created through unorthodox means. This means while his videos are interesting, his music lacks mass appeal and can sometimes be challenging. A good example of this is his video entitled “Making music with actual sounds from Mars” (Huang, 2018) while the title is very self-explanatory, it does exemplify the outlandish ideas which usually serve as a basis for his creativity.

So how did Andrew achieve mainstream popularity as a YouTuber then, if not through musical following? Through interest pieces and manipulating the YouTube suggested video algorithm mentioned earlier (the algorithm powered by data collection on YouTubes userbase). In an interview with KVRaudio Andrew said “I just did the videos and people came. I would say that some of the videos I have done, I have had in mind that they would be an outreach video. Most of the videos that I do are just something that I thought of someday where I’m showcasing a part of something I’m working on that I think will be interesting to my audience” (KVR Audio, 2019) he then goes on to talk about the popularity of fidget spinners at the time and mentions “I made a couple of videos where I put the fidget spinners front and centre. And those got about a million views each.” (KVR Audio, 2019).

Finally, when questioned further on the topic he states “The more common ones for a music channel would be to do a cover of whatever the hottest song is at the time. That’s what a lot of music channels do to keep new viewers finding them.” (KVR Audio, 2019)

All of this paints an image of a content creator, trying to focus on popular trends and topics. No different to any other content creator but with his own, music based, twist.

Joji

In the context of a creator who rose to popularity through content designed to take advantage of the system, it may be worth examining another success story which exists as the antithesis to this.

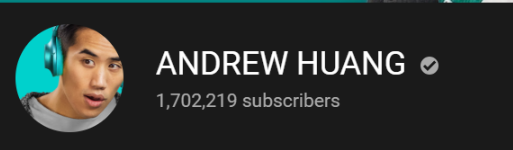

Joji (A.K.A. Pink Guy or FilthyFrank) is an artist by the name of George Miller, whose internet presence was never particularly closely tied to music until recently. The early content which established his branding and personality were surreal to put it lightly.

While FilthyFrank often created music related videos on YouTube (outlined above from his earliest videos) his usual content was a mixture of dicey inappropriate humour and outlandish absurdism the likes of which hasn’t been captured before or since.

This comes back to one of the core principles of online popularity mentioned earlier, branding. His first major success came from the beginning of the “Harlem Shake” meme which swept the internet in the early 2010s, since then he’s taken the fanbase he earned in online comedy and used it to transition over to music under the stage name: Joji.

While his above videos may sit on between 1 million to 2 million views on average, after 5 to 6 years of being on YouTube, he currently gets almost 6.5 million listeners on Spotify each month, many of which may be listening to multiple songs.

However, this outrageous humour did land him in trouble throughout his career on YouTube, and while he doesn’t have a presence on YouTube as a musician (outside of his label; 88rising’s channel)

as a comedic YouTuber his videos were routinely a part of active controversy which saw them frequently being removed from the site.

The paradox of this being that YouTube routinely has 300 hours of content uploaded every minute in our current age. (Omnicoreagency.com, 2019) this serves as a basis for the most interesting issues in social medias. These companies do not have the resources to manually sift through each video and censor each one by hand, of course an AI can do that but these aren’t always accurate.

Only once a YouTuber get’s big enough to have an audience do they routinely run into trouble, however the more YouTube tries to censor users like FilthyFrank, the louder their audience becomes and as such attracts more people.

To outline the timeline of his success as simply as possible, he first created content with absurdist humour under Filthy Frank and started posting shock humour music as Pink Guy, finally he began releasing music under the name Joji which he has referred to himself as “serious music” in one of his songs “Rice Balls” – Pink Guy (TVFilthyFrank, 2015) when writing for BEAT (one of countless new gatekeepers which have emerged in the form of independent news outlets and blogs focused on music since the creation of the internet) Judy Mae writes about George Miller “if he teaches us anything, it’s that brand segregation is a must”.

Finally based on these two archetypes of online popularity, a structured 3 year plan for artist development.

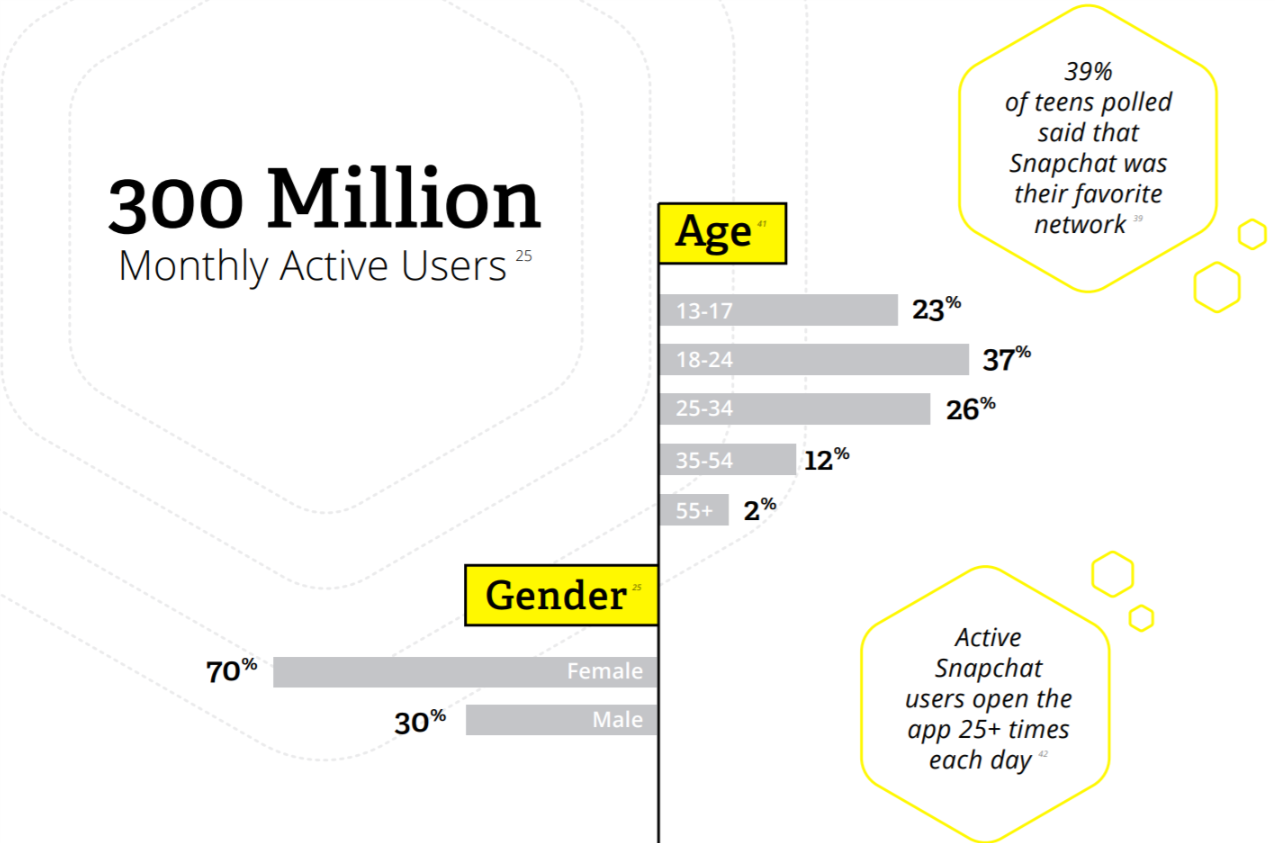

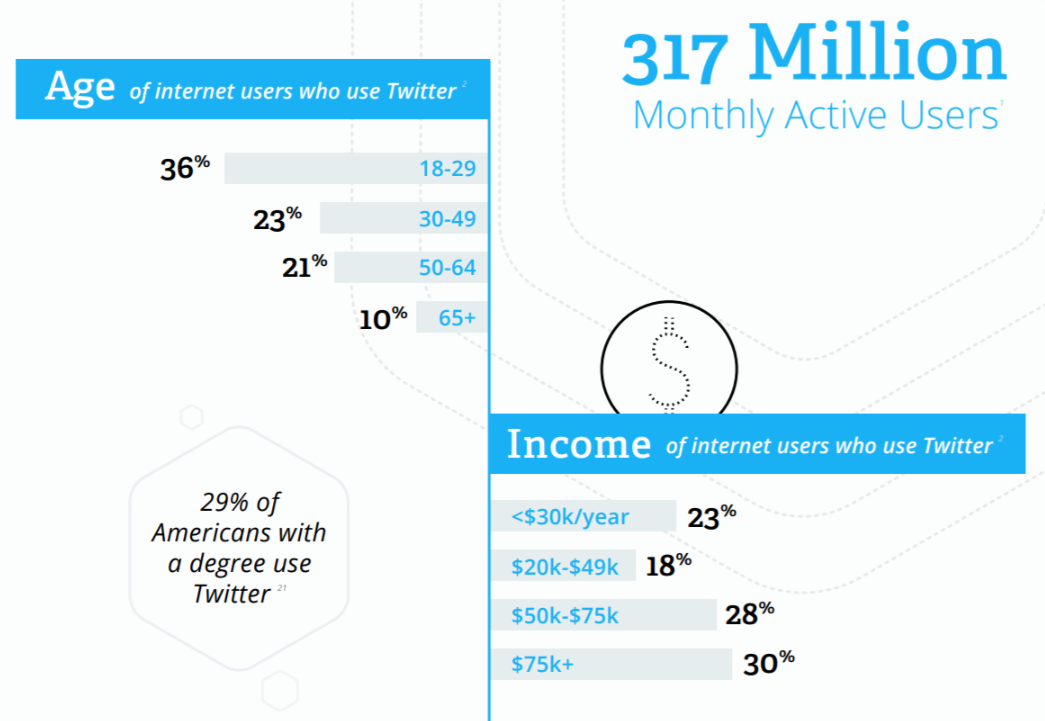

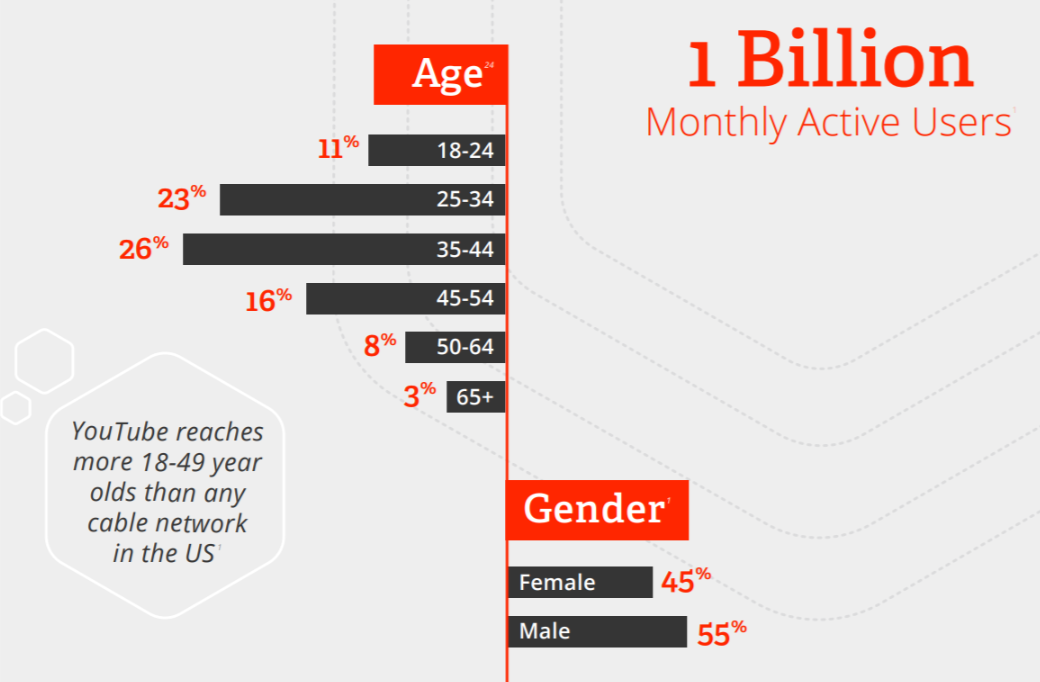

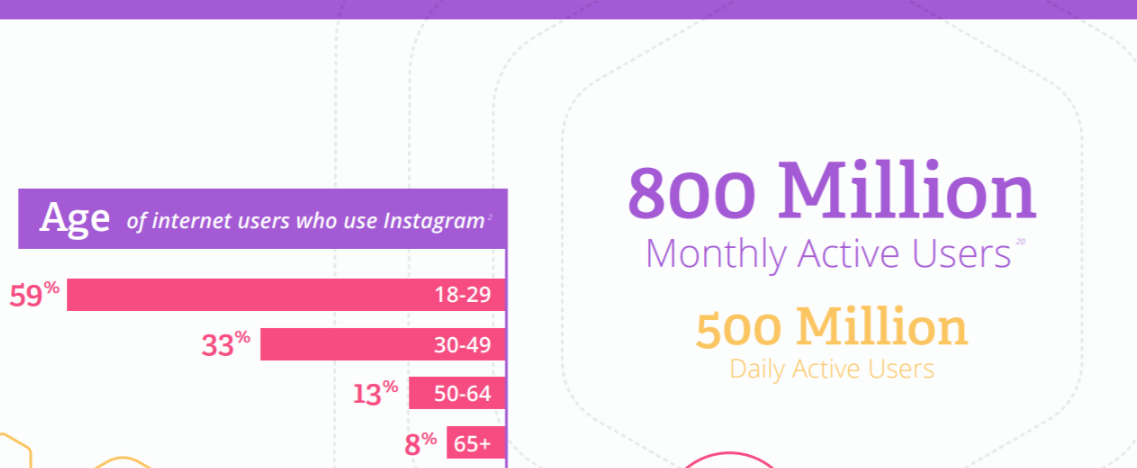

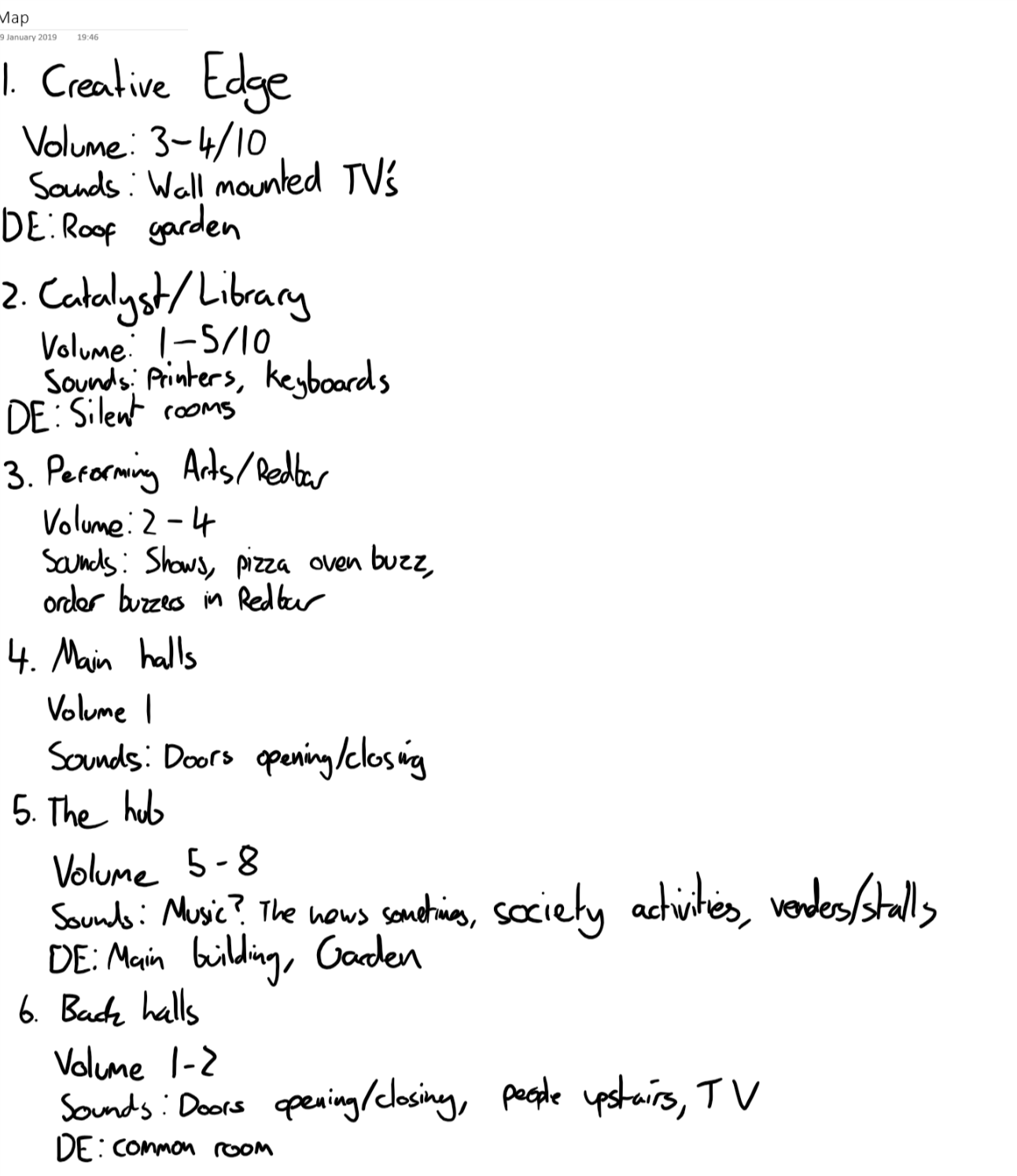

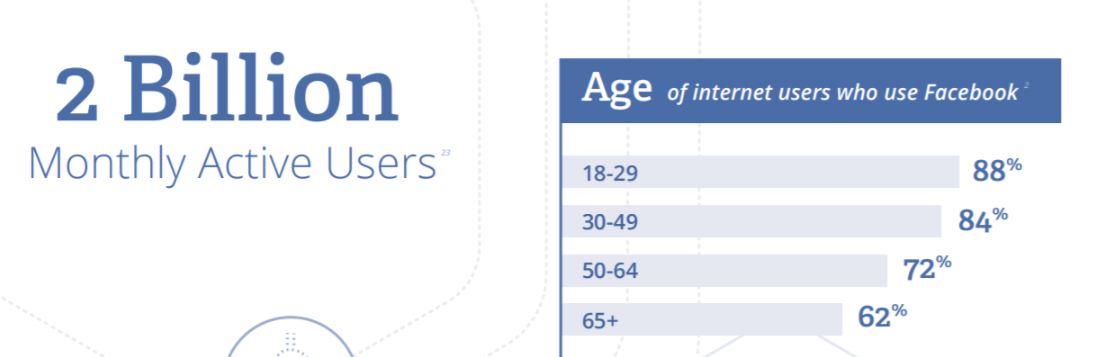

Each social media have their own demographics, so for an independent artist struggling with time management it may be important to specify down to specific social media to meet their target audience. For this purpose:

Above we have a series of images (Spredfast, 2018) which highlight the age representation on each current social media. The full file outlines platform usage by wage, age, gender, time and device.

Our Artist

Let’s call our artist X,

he’s white, male, brown hair, average height. He’s currently making music in

his bedroom.

Firstly, examine what scenes emerging artists are currently coming from.

Recently artists such as Still Woozy, Wallows and Mac Demarco (Who are all

white men with brown hair and average (or above average) height) have been

emerging out of the Bedroom Pop scene, a scene which has recently gotten a

Spotify playlist which is getting new editions each week. So our artist should

create bedroom Pop.

Given that genre, creating an “image” for the artist is key, one of the key features

of this music scene is eclectic fashion highlighted in Still Woozies “Goodie

Bag” (displayed right, (Still Woozy, 2018))

This is the basis for our artists image, except with prominent branding.

Perhaps a t-shirt with artist logo visible across the chest or a distinct hat?

Now that the idea of the artist has been established, consistent branding must

be created for social media and alongside this, a webpage which directs to

social media. Branding featuring similar colour palettes to these videos and

fonts which reflect the feel of the music being created.

The Year Plan

This plan aims to combine the humour which made FilthyFrank so shareable, with the musical enthusiasm which has make Andrew Huang so popular with other musicians into an image based on a current emerging scene.

Post a simple, absurdist cover which sodomizes lyrics; similar to Nullberry’s, “Take Me Home, Country Roads except I lose all grasp on reality during the chorus” (Nulberry Official, 2019).

From here, begin making more comedic content pertaining to music, possibly branching into other communities like Seth Everman and his surreal pop culture/music hybrid comedy. (SethEverman, 2019) or possibly something similar to Hovey Benjamin and his pop culture filled slug fests (Hovey Benjamin, 2017).

Share this content via the established social media and feature your website at the end of each video, the content should be in small, easily digestible playtimes for maximum share potential. (The trick here is creating content that users want to send to one another, hence the humour which is something people innately bond over.)

Begin local performances, at open mics/ any gigs which pay. Make sure to talk to your crowd both on and off set and plug your music once at the end of set. Don’t be afraid to promote this more one on one.

As local buzz starts to generate and fanbase slowly grows, drop a bedroom pop track with subtler comedic elements but more focus on musical elements and catchy-ness. Perhaps tease upcoming release?

Continue posting personable content regularly on social media while releasing slightly more complex ideas as videos on YouTube.

Keeping all of this up a fanbase should start to grow, around this time possibly release a music video for your song with the most promise, make sure to include the air of share-ability again, and to keep the content on brand and standing out.

Finally, with a reasonable following and a great portfolio, begin seeking representation.

Bibliography

Hovey Benjamin, 2017. Fidget Spinner / Vape – Hovey Benjamin (“Official” “Music” Video) [online video] from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2IecNbQNU1M [Accessed 6 May 2019]

HUANG, A., 2018. Making music with actual sounds from Mars [online video]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iovUGHuuIyo [Accessed 5 May 2019]

Kaitajärvi-Tiekso, J. (2016). ‘A Step Back to the Dark Ages of the Music Industry’: Democratisation of Record Production and Discourses on Spotify in Kuka Mitä Häh?. Networked Music Cultures. [online] Available at: https://www.academia.edu/37250869/A_Step_Back_to_the_Dark_Ages_of_the_Music_Industry._Democratization_of_Record_Production_and_Discourses_on_Spotify_in_Kuka_Mit%C3%A4_H%C3%A4h_ [Accessed 6 May 2019].

KVR Audio. (2019). Andrew Huang Interview: Launching a music career on social media. [online] Available at: https://www.kvraudio.com/interviews/andrew-huang-interview-launching-a-music-career-on-social-media-44512 [Accessed 6 May 2019].

Nulberry Official, 2019. Take Me Home, Country Toads except I lose all grasp on reality during the chorus [online video] from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gTcGr7wZ9lo [Accessed 6 May 2019]

O’Reilly, K. (2009). Key Concepts in Ethnography (SAGE key concepts). Sage Publications.

Omnicoreagency.com. (2019). YouTube by the Numbers (2019): Stats, Demographics & Fun Facts. [online] Available at: https://www.omnicoreagency.com/youtube-statistics/ [Accessed 6 May 2019].

Ramaut, S. (2014). How Beginning Indie Bands Should Promote Themselves Using Social Media.

Sanchez, D. (2019). What Streaming Music Services Pay (Updated for 2019). Digital Music News. Available at: https://www.digitalmusicnews.com/2018/12/25/streaming-music-services-pay-2019/ [Accessed 8 May 2019].

SethEverman, 2019. baldo mode [online video] from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wBBOcCe9Mak [Accessed 5 May 2019]

Spredfast. (2018). The 2018 Social Audience Guide. [online] Available at: https://www.spredfast.com/social-media-tips/social-media-demographics-current [Accessed 5 May 2019].

Still Woozy, 2018. Goodie Bag [online video] from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zL3wWykAKfs [Accessed 6 May 2019]

TVFilthyFrank, 2015. RICE BALLS [online video] from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LeMVDuIO3J0 [Accessed 5 May 2019]